8 Groups of People That Didn’t Like What They Saw (or Heard) in a Superman Story

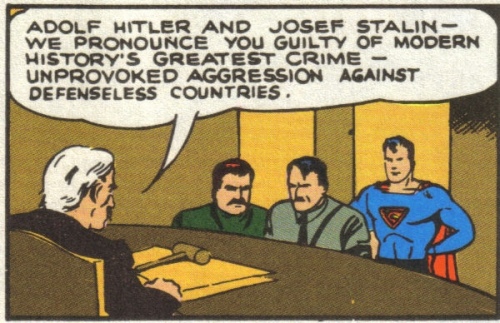

1. The Nazi SS

I know, right? Actual Nazis had a bone to pick with Mr. Truth, Justice and the American Way? Go figure. Back in 1940, before the U.S. entered the Second World War, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster created a two-page strip for Look magazine that showed Superman single-handedly ending the war by arresting Hitler and Stalin for “unprovoked aggression against defenseless countries.” Not long after, an article in Die Schwarze Korps, the official newspaper of the SS, blasted the story and mocked Superman as a symbol of American aggression. The fact his two creators were Jewish didn’t escape the unknown author’s notice, either, and the article hurled a few choice epithets at them while accusing them of corrupting American youth with suspicion and hatred of others. It’s hard to believe the Nazi propaganda machine would have even known, much less cared, about a strip starring a two-year-old comic-book character — but you can imagine how thrilled those two kids from Cleveland must have been to find out their creation was attracting that much attention so early in his career.

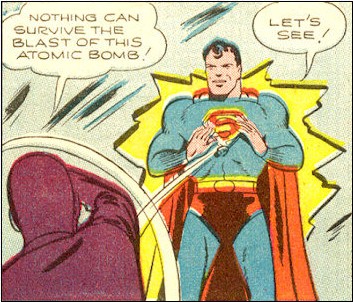

2. The U.S. government

Loose lips sink ships, as the saying goes, which is why governments at war tend to be super-sensitive about the mention of certain words in public. By the time the U.S. entered the Second World War in December 1941, comics were already proving to be a valuable propaganda tool, painting enemy soldiers as sub-human monsters while encouraging young Americans to organize scrap drives and buy war bonds. The War Department kept a close eye on the stories that comic publishers were putting out, with allocations of tightly rationed newsprint proving to be a mighty persuasive tool for getting publishers to play ball. One Superman story, “The Battle of the Atoms,” was delayed a few years because it contained the words “atomic bomb” — and while Luthor’s device looked nothing like what eventually came out of the Manhattan Project, officials didn’t want Americans thinking about atomic bombs until the government was ready to say it was working on them. (A postwar story about Superman filming an atomic bomb explosion for the U.S. military was also delayed a year or so, this time because government officials didn’t want a story about atomic bombs appearing so soon after the U.S. dropped two of them on Japanese soil.)

3. The U.S. government (again)

In 1945, with the war still on but drawing to a close, the War Department again contacted DC, this time about the Superman newspaper strip written by Alvin Schwartz that mentioned a “cyclotron” as a sci-fi gizmo. This was a concern because that was the name of a piece of equipment used by scientists involved in atomic research, and the government was keen on keeping a lid on any mention of atomic energy that might lead to other countries developing their own nuclear weapons. (There was also the concern, not entirely unjustified, that the American public wouldn’t take nuclear energy seriously if they thought the science behind it was inspired by comic books). After a brief investigation by the FBI, DC agreed to censor the strip. Schwartz himself didn’t find out about the investigation until after that war; when he was told about it, he revealed where he got his information about cyclotrons — an article from an issue of Popular Mechanics that appeared in the 1930s.

4. The Ku Klux Klan

In June 1946, the radio program The Adventures of Superman broadcast “The Clan of the Fiery Cross,” a 16-part storyline in which Superman (voiced by Bud Collyer) battled a group of racists who were meant as an obvious stand-in for the Ku Klux Klan. What listeners of the show didn’t know was that a lot of the passwords and rituals used by the show’s fictional villains were fed to the show’s writers by Stetson Kennedy, a man who infiltrated the KKK to expose them. While passing along information to some of the notable journalists of the day, Kennedy also contacted Adventures of Superman producer Robert Maxwell, who was happy to help Kennedy’s Anti-Defamation League de-fang the hate group by reducing its tenets to the silliness of comic-book villains. How effective the show was in curbing the Klan’s activities is hard to say — it’s not as if the group made its annual membership numbers publicly available — but it’s easy to imagine them at least a little irritated to have their secrets aired in public… and on a kids’ show, of all places, where their glorious struggle for racial purity was played for laughs (as well it should).

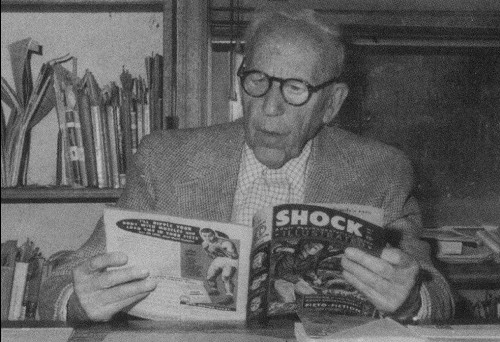

5. Anti-comics moralists

Of course, the parents, teachers and dime-store psychologists went after the crime comics, with their over-the-top violence and horrific acts of sadism. Of course, they recoiled at the comic books with the ghouls and the zombies and the gruesome desecration of corpses on every page. Of course, they went after the sci-fi comics with their suspiciously communist-sounding ideals, like questioning the inherent goodness of American (or white) superiority. But Superman? Mister Truth, Justice and American Way himself? Getting parents to rail against crime comics was child’s play, but Dr. Fredric Wertham proposed that all comic books were inherently harmful to children. The superheroes might have seemed okay when they were selling patriotism during the war, but things were different in Eisenhower’s America, a place where anyone who stood out from the crowd was viewed with suspicion. So Wertham and like-minded people went after the superheroes, writing books and articles about Wonder Woman’s sadomasochism, Batman and Robin’s implicit homoeroticism, and Superman’s grandstanding and fascist tendencies. But those weren’t his worst sins, according to the good doctor:

Actually, Superman (with the big S on his uniform — we should, I suppose, be thankful that it is not an S.S.) needs an endless stream of ever new submen, criminals and “foreign- looking” people not only to justify his existence but even to make it possible. It is this feature that engenders in children either one or the other of two attitudes: either they fantasy themselves as supermen, with the attendant prejudices against the submen, or it makes them submissive and receptive to the blandishments of strong men who will solve all their social problems for them — by force.

How did DC respond? Executives went around the country talking to PTA groups about how great comics were in encouraging kids to read, and the company played ball when the Comics Code Authority came into effect, making sure that none of its heroes ran afoul of the new rules. (Running lots of PSAs in their comics with Superman extolling American values didn’t hurt, either.) But when the Adventures of Superman TV show hit the airwaves in 1952, its huge success did more to cement Superman’s status as a kid-friendly character than anything else, and the critics moved on to easier targets.

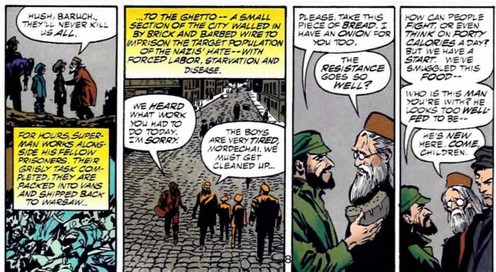

6. The Jewish Anti-Defamation League

To celebrate Superman’s 60th anniversary, in 1998 DC published stories in each of his four titles that took place during different decades of his career. Superman: The Man of Steel, for instance, saw our hero embracing his champion-of-the-oppressed roots by saving lives in Nazi-occupied Europe during the 1940s. Quite a bit of detail went into describing the harsh conditions of life in the ghetto… except for the one small detail of who actually lived in those ghettos. In fact, as some people noticed, the words “Jew,” “Jewish” and “Holocaust” (as well as other words denoting any cultural group, like “Catholic” or “German”) never once appeared in the multi-issue story. When asked to explain, one of DC’s editors said they went with phrases like “target population” and “murdered residents” to avoid offending anyone; the last thing DC wanted was for younger readers to taunt their Jewish classmates with ethnic slurs picked up from Nazis in a Superman comic. Not good enough, said people with an interest in remembering what happened back then: “You start out with a very good idea to teach comic-book readers a little bit of history, then you turn it on its head by refusing to acknowledge who the victims are,” Emory University Holocaust scholar Deborah Lipstadt told New York Jewish Week. The Jewish Anti-Defamation League also objected, saying it was insulting to the victims (and not just the Jewish ones) not to acknowledge the reasons why they were targeted. An apology was quickly issued and accepted.

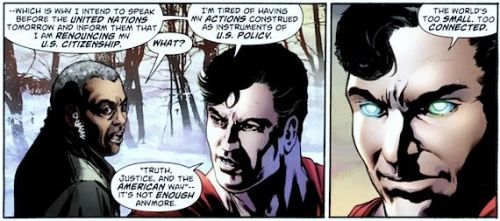

7. Pro-American pundits

If there’s any one group that you would think would have no problem with Superman, it would be the America-first crowd who tend to cheer every time they see that part of Superman II where he flies the American flag. But in 2011, Superman — or, rather, one writer’s interpretation of how Superman should be perceived — managed to get even those guys riled up. In Action Comics #900, a nine-page story finds Superman standing between Iranian police and protesters for 24 hours as a way of showing solidarity with the protesters. When his actions are denounced as an American-sponsored act, he tells the president’s National Security Advisor that he plans to publicly renounce his citizenship so that he can do what he feels is necessary without his actions being “construed as instruments of U.S. policy.” One could quibble with the timing of the story or the need to inject real-world events into superhero stories, but some people weren’t interested in those kinds of discussions. “I’m disturbed by this whole globalist trend,” said Fox News mainstay Mike Huckabee. “You know what, I think we ought to be teaching young Americans that they’re young Americans. That it means something to be an American.” Another commentator for Fox News said Superman had been “hijacked” by Lex Luthor or “by one of those leftover hippies from the ’60s who now teaches at an Ivy League university, or at Berkeley” because “the real Superman would never abandon America.” In response, DC co-publishers Dan Didio and Jim Lee said the character is and always will be a red-blooded American despite his global focus: “He remains, as always, committed to his adopted home and his roots as a Kansas farmboy from Smallville.”

8. Gay-rights advocates

For a change of pace, let’s look at a Superman story that didn’t even have to get published to get a lot of people upset. When DC announced in 2013 that sci-fi writer Orson Scott Card would co-write an issue of The Adventures of Superman, thousands of people signed petitions demanding DC sever its ties with Card, comic retailers vowed to refuse the book, and artist Chris Sprouse backed out of the project citing the immense media reaction it attracted. Why the fuss? Card is an outspoken opponent of homosexuality and gay marriage; he joined the board of directors for the National Organization for Marriage in 2009 and called gay marriage a “collective delusion,” telling an interviewer it’s “hard to find a ridiculous enough comparison” to the idea. He also took aim at “dictator-judges” who would force laws granting marriage to “tragic genetic mix-ups.” Not surprisingly, DC distanced itself from that kind of talk and dropped Card from the project, leaving him and his followers to fume about how unfair it is they can’t go around in this day and age calling whole groups of people the unfortunate products of “rape or molestation or abuse” without everyone getting all huffy about it and demanding their right not to enrich an unapologetic bigot. “Where is the tolerance for those of us who choose to be so virulently intolerant?” they screamed as one. “Ha! Bet you liberals didn’t see that one coming, did you?”